Originally published at: RaceRanger Age Group Test Offers Insights on Future Potential and a Glimpse of Athlete Drafting Data - Slowtwitch News

RaceRanger, the draft-detecting technology developed by former pro triathletes James Elvery and Dylan McNiece, took the next step in its evolution last month when 255 age group athletes used the device at Challenge Wanaka.

Elvery and McNiece have been working on the project since 2014, but got serious about it in 2017 thanks to backing from World Triathlon. Jimmy Riccitello, IRONMAN’s head referee, has been working with RaceRanger since 2018. The devices have become a mainstay at pro races over the last couple of years thanks to their use at Professional Triathletes Organisation (PTO) races and the IRONMAN Pro Series last year. This year RaceRanger will provide its services to 37 or 38 pro races around the world.

The RaceRanger technology features two electronic units placed on each athlete’s bike, one at the front and one at the rear. The rear unit has a light which serves up signals to the rider behind, letting them know if they’ve entered the draft zone of the rider ahead of them. The front device measures the distance to the rider ahead, but can also show warning and penalty signals from referees. Accurate to 10 cm over 30 m, the RaceRanger system measures 10 times a second.

Athletes and officials have praised the system for providing concrete feedback on where they are in a draft zone. It’s become a mainstay at pro races, but ultimately for the RaceRanger technology to really become profitable, it will need to become a part of age group racing, too. The question has always been, would athletes be willing to pay a bit more for a device that would help prevent drafting in their race? Would race directors see that it provided enough value so they would be willing to pick up the cost? Could the added expense be split between the two?

Before all of that even becomes an issue, though, the first step is to ensure that RaceRanger can be scaled to support a large race of, say, 3,000 athletes. Hence the trip to Wanaka last month to test things out.

According to Elvery, the first run was a success. The RaceRanger crew were able to figure out some of the “pain points” in the process. They had six people on hand to help fit the 255 units on the bikes. (The plan is to start having athletes put their own devices on in future.) There was only one bike that they couldn’t fit a device to, which Elvery said was a pleasant surprise. (And, if they’d had more time to move the athlete’s rear-mounted water bottle, they could have got the unit installed.) Another happy success was that while, for pro races, each unit is turned on manually, in Wanaka the RaceRanger engineers were able to have the devices turn themselves on before the race, saving a lot of running around. Since not everyone in the race was equipped with a RaceRanger, there were some issues of with bikes interfering with the process – “We need to have it on all the bikes for it to really work,” Elvery said.

“The feedback was overwhelmingly positive,” Challenge Wanaka race director Jane Sharman said. The race officials were equally as happy with the test.

Coming to a Race Soon?

Despite the success and positive feedback from the first age-group run through, there’s no plans to implement this technology at more age group races in 2025. There are a few steps RaceRanger is looking to implement before its ready to tackle a potential 3,000-strong age group race.

The next step in the development of the RaceRanger device is two-fold: the goal is to have just one device on each bike, and each unit will have an enhanced chip so it can provide more accurate tracking data. That will allow the devices to provide precise tracking information (as opposed to the estimated live tracking gleaned from timing points). In addition to ensuring that your loved ones or fans aren’t still having a coffee as you fly by, that info could be a valuable safety tool, allowing race directors to get help to athletes more quickly if necessary.

That data, if it could be provided “live” to the officials, would also make it possible to track athletes drafting patterns without being right on the scene. An official could get an alert that an athlete has spent an excessive amount of time in the draft zone, and move to their position to check things out.

Current Reporting Abilities

Even without the next-generation of the RaceRanger device, the company has been providing both IRONMAN and the PTO with detailed race reports after each race. Using the data from the race in Wanaka, RaceRanger has provided spreadsheets with those reports (they generated anonymous names to ensure no one’s information could be identified.)

The report provided a massive amount of data: Here is some of the interesting stats we got from it.

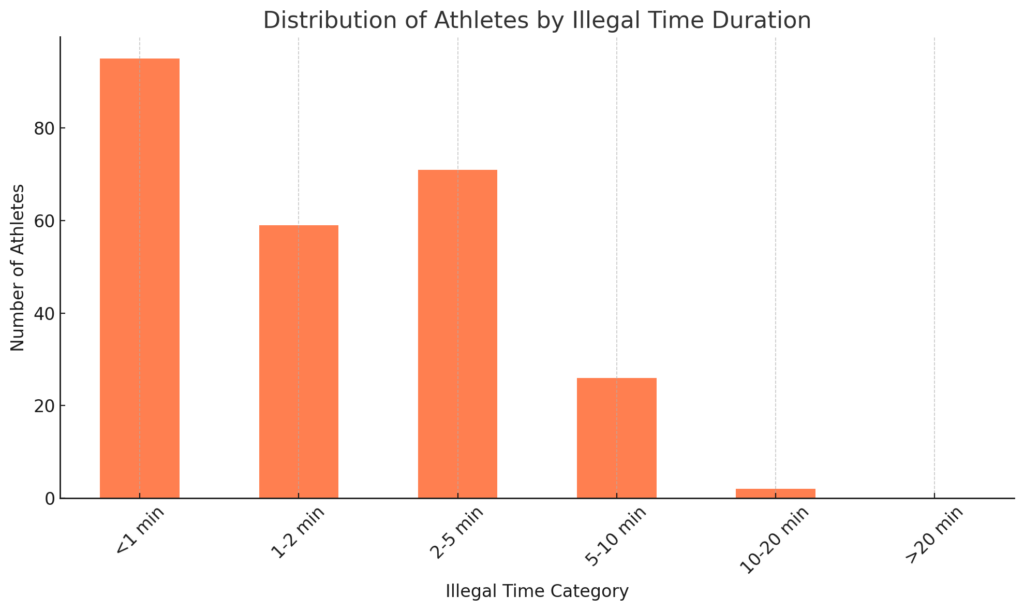

- Illegal Time: Anytime the athlete breaks the drafting rules. The time in this column varied from 1 second to 24 minutes and 42 seconds. This could be:

- taking longer than 25 secs to overtake

- taking longer than 25 seconds to drop back

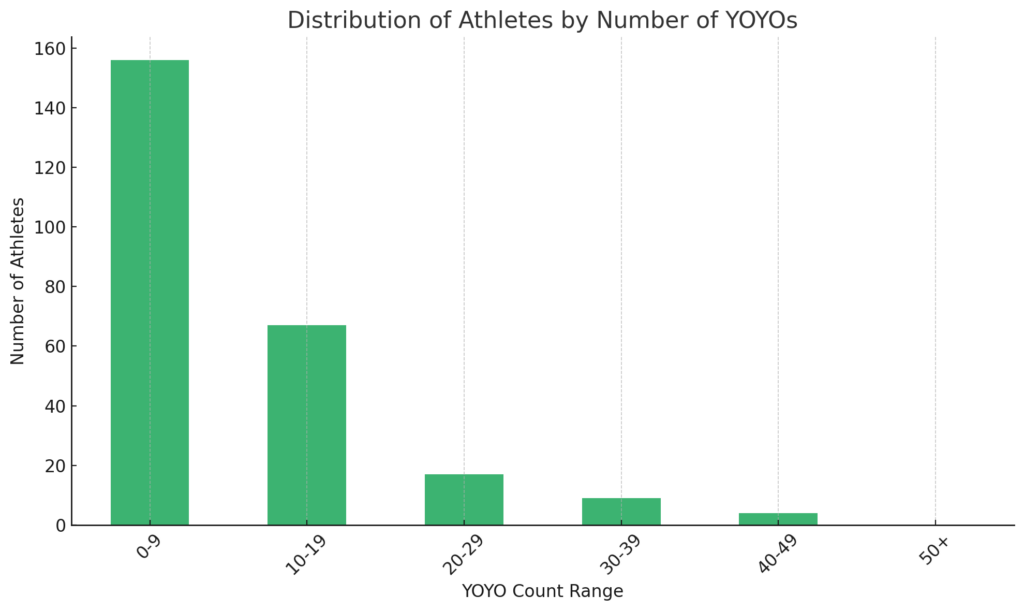

- anytime they enter a draft zone and then drop back out the back (yo-yo)

- For example: Taking 30 seconds to pass, earns you 5 seconds towards your illegal time score.

- A 10-second yo-yo in and out the back of a zone would earn 10 seconds

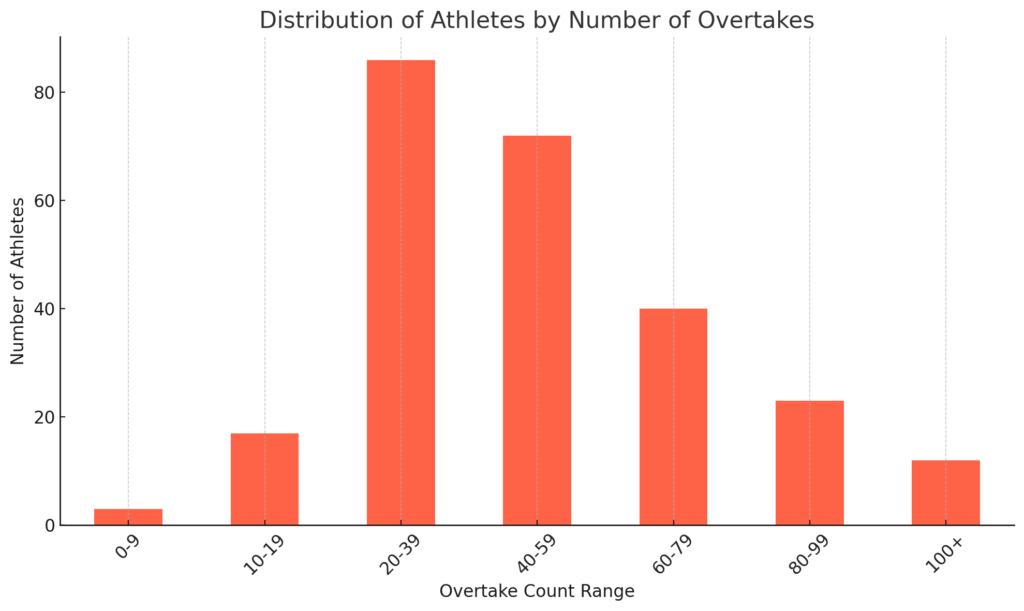

- Overtakes: The athletes overtake count for the whole race. The high in this category was 184.

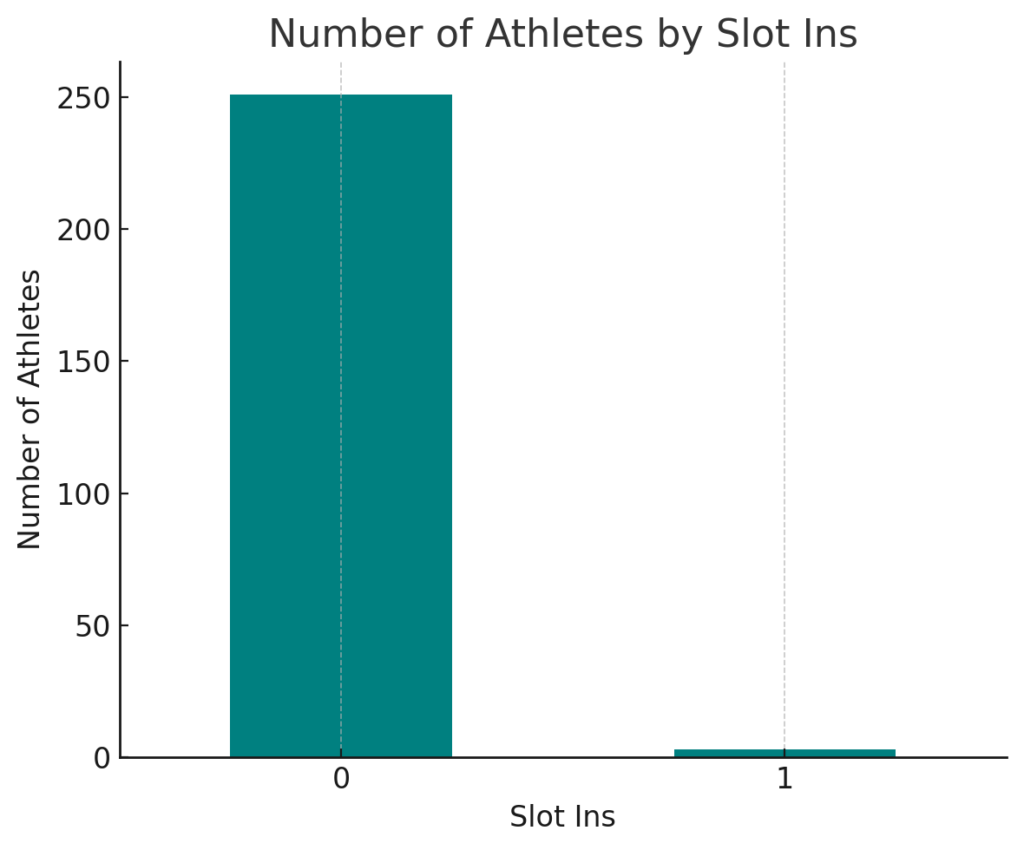

- Slot ins: Instances where they slotted in front of t a rider into a gap that didn’t exist, and didn’t complete a pass. This is most interesting for pro competitions. As you can see from the race in Wanaka, this isn’t a real issue for age group athletes. (At least in this race.)

From the data provided from Wanaka, the “worst offender” spent 24 minutes and 42 seconds in the draft zone. That athlete also “yoyo’d” – entered a draft zone and then dropped back rather than passing – 31 times. The data showed that the athlete spent 9:42 on one athlete’s wheel, including one stretch for that lasted for 2:11.

The “least” offending racer spent a grand total of a second riding illegally, never yo-yo’d and managed to overtake 17 people.

The folks from RaceRanger believe that this type of information would be of interest to athletes and officials alike. With enough data, athletes could even have the equivalent of a “drafting passport” developed, showing an athlete’s general riding habits.

RaceRanger can also create individual reports that also provide location data so officials know exactly where on the course an infringement might have taken place. From that information, an official could identify that the incident might have happened going through an aid station or another area of the course where a penalty would not be given.

Letting RaceRanger Make the Calls

At this point the RaceRanger technology is used as an aid for race officials. Elvery acknowledges that there’s a long way to go before athletes and officials trust the technology to the point where they’d be willing to have calls made based on the data provided. It feels like a similar process to the Hawk-Eye technology used for tennis officiating now. Originally designed for television of cricket in 2000, it eventually became the basis for a challenge system in tennis starting in 2006. Over the last few years we’ve seen the technology incorporated into professional tennis on a full-time basis.

The bigger question is whether or not athletes would be willing to pay anything extra to be able to use the equipment. A recent survey run by Tri-Mag.de found that middle- and long-distance athletes appreciated the potential of the RaceRanger technology more than sprint- and Olympic-distance athletes. Those who were in favour of it said that they’d be willing to pay roughly 16 Euros to use the device at races. Elvery said that’s “about what we would need to charge.”

Certainly age-group competitors competing at the front of the pack would be keen to see this technology take off and be implemented at races, especially at world championship and qualifying events for those championships. Events geared towards recreational and beginner athletes probably won’t see the value in adding this technology at this point. We’re at least a year, and more likely two years, away from seeing how it will all play out.

[/um_show_content]