Originally published at: The Garmin Ecosystem - Slowtwitch News

What Is An Ecosystem Company?

Garmin acquired FirstBeat Analytics in June of 2020, the news made relatively little impact. I think most of that was timing, as it came during the peak of the pandemic lockdown. It also wasn’t much of a change for end users, as Garmin had already been using FirstBeat – as a licensee – in its products for over a decade. But the acquisition represented what – in hindsight – seems to have been a clear shift in Garmin’s fundamental approach to its fitness business. Owning FirstBeat allowed Garmin to become an “ecosystem” company rather than simply a product company. Garmin now makes systems. And the products it makes are designed to work within those systems. In some cases, their products only really make sense when you view them through the lens of the system rather than as a standalone offering.

As the FirstBeat, Tacx, and Vector (power-meter pedals) acquisitions show, Garmin has generally sought to expand its ecosystem via acquisition. It certainly has made some truly innovative products – like the Varia Radar – but its real genius has been finding companies that can easily meld into its ecosystem and help expand its reach. The other company that has followed a similar trajectory of moving from a product company to an ecosystem company, largely on the back of acquiring companies and then using those acquisitions to build a richer and more comprehensive ecosystem is SRAM. The SRAM of today looks nothing like the SRAM of 2006/2007, when they launched their first RED road grouppo. SRAM today is an ecosystem company. Quarq was probably its most important acquisition, not because of the powermeters, but because of acquiring Jim Meyer, who now leads all things digital, which – for SRAM – is basically everything. Even more interestingly, SRAM doesn’t just not resemble itself anymore; it also doesn’t resemble Shimano either. Shimano, meanwhile, has remained largely unchanged in terms of the type of business it is.

Unquestionably, the most important fittech acquisition of this millenia was Garmin’s 2006 acquisition of Dynastream, the creators of the ANT protocol. Garmin was just starting to get into fittech with its Forerunner line – I had one of those classic pill-shaped Forerunner 201s. And I think they saw that connectivity was really the key to making fittech work. The Edge 500 wouldn’t come out for a few more years, but I am sure Garmin was already imagining such a product. Notably, after acquiring Dynastream, they initially tried a licensing model with ANT. They quickly pivoted though, open-sourcing it and starting the entirely separate ANT consortium – thisisant.com, which was certainly the right decision to spur widespread adoption. While BLE has finally caught up – and some might say surpassed ANT, owing to its inclusion on mobile phones, ANT really set the stage for the wireless fittech ecosystem. It was low power. And it just worked. I still basically don’t really trust BLE, and I will always opt to pair via ANT for sensors that support both protocols. In 15 years of using it, ANT+ has just been bulletproof across all manner of devices, both measuring devices and computers/watches. Without ANT, none of what followed would have been possible, since ANT opened the door for devices to talk to each other. It allowed an ecosystem to grow.

The ecosystem approach was almost certainly a case of imitation and self-preservation as well as innovation. Garmin increasingly has to compete with the exemplar ecosystem company – Apple. It’s especially interesting to see Garmin not only protecting their areas, but also (sort of) moving into Apple’s Garmin has GarminPay, allowing you to pay with just your watch at wireless terminals. Garmin also recently launched Garmin Messenger, which allows you to communicate using an InReach device when you are in the backcountry with people on their phones. I think part of the reason why Apple has struggled to make more inroads with serious athletes is because Garmin has so aggressively – and so effectively – continued to make the Garmin ecosystem more feature rich.

I have had an idea percolating in my mind for a couple years about how to write about this. It first came to me when Garmin introduced the Varia Radar. I became more convinced of the shift in Garmin’s approach when they acquired Tacx in 2019. And then followed that up by acquiring FirstBeat. But I never could find a hook. It felt overly editorial – “this is this thing that I see happening.” It lacked the experiential quality that I think is essential to good storytelling. If you want to know the nuts and bolts of how a fitness product works, it’s essentially impossible to beat Ray Maker of DC Rainmaker. And the pure editorializing just doesn’t feel all that compelling. But when I started mountain biking with my oldest son this past winter and decided to return to triathlon and do my first XTerra race, I had an idea about how to tell this story. I’ve been an on-again-off-again user of various fitness platforms for years, but the one constant has been Garmin Connect. Since 2009, I’ve tracked virtually every run I’ve done using a Garmin Forerunner. And since 2010, I’ve tracked virtually every ride with a Garmin Edge. I’ve since resorted to using just a Forerunner for everything, something I talked about my article about how A Clean Cockpit Is More Fun.

Could This System Help Me? Can It Help You?

While I had made the decision to ignore pretty much all data during my rides, I became increasingly intrigued by the data that Garmin was offering after them. Garmin clearly had a lot of ideas about what I should be doing for training, how I should be recovering, and more. I wondered, what if I actually listened to some of them? What if I actually dove into the Garmin ecosystem as part of training for an XTerra. I’ve always been skeptical of HRV as a standalone metric, but what about its utility when rolled into a larger package that also has detailed insights into your actual training? I figured at the very least, it would give me something to obsess over now that I’d committed to not obsessing over power.

This nicely coincided with the major overhaul – first seen via public beta – of Garmin Connect, both the web app and the phone app. Garmin Connect had always seemed like a non-priority for Garmin. They seemed generally happy to cede that ground on the social side to Strava and on the fitness and tracking side to more specialized sites like TrainingPeaks. Connect was always “good enough,” but not really much more. But with the recent update, it was clear that Connect’s importance to the ecosystem was becoming clearer, and it could no longer afford to be ignored

In deciding which device to use as the backbone for my experiment, I debated heavily between the Forerunner 965 and the Epix Pro. Since FirstBeat’s analytics tech is the foundational piece here, I was strongly tempted to go with the Epix 2, which has the newer Elevate 5 sensor, which offers skin temperature reading, over the Elevate 4 in the 965. And, of course, it’s just newer. So any attempt to glean insight about the usefulness of buying into Garmin’s ideas about training seemed like it ought to rely on the latest hardware. But having owned a Fenix, I also much prefer the fit and feel of the lighter Forerunner watches. I ended up requesting a 965, which Garmin graciously provided for this article.

An article like this would have been a lot more difficult before Garmin introduced TrueUp, which incorporates all workouts from all devices and some key partners into your training data. You could do it if you just wore your Forerunner for everything – as I do, but you’d have to record your indoor sessions on it as well. And if you prefer to use a cycling computer, it makes sense to use that for cycling rather than needing to use the watch. TrueUp was maybe the first indication that Garmin Connect was going to play a larger role than it had, as it now served as the aggregator and disseminator of information. I can see all my workouts on my watch, whether or not I’ve actually recorded them on my watch.

Given that I was also training for an XTerra, I also was curious what sort of insights I’d get from using a Garmin powermeter. While the heart rate data is primary, Garmin uses power data on the bike to estimate VO2Max, which is part of how it calculates fitness trends and training efficacy. For running, it’s a combination of heart rate data and pace. Garmin provided me with a pair of the Rally XC200 dual sided pedals as well.

Sleeping With A Watch On Kind Of Stinks

The most difficult part of this whole experiment for me was getting used to sleeping with a watch on. Overnight data is required for FirstBeat to calculate HRV, which is a requirement for getting “Training Readiness” information. You can get the Training Status data without it – that’s based primarily on your actual training data; but even this is somewhat limited as Garmin uses HRV data to indicate periods of “Strain,” which is low HRV combined with declining VO2Max. So I had to learn to sleep with a watch. This made me doubly glad to have the 965, as it’s a lot lower profile than a Epix. After trying unsuccessfully to wear the watch through the night – I’ve literally never slept with my watch on – and getting abysmal sleep scores as a result, sleep scores that were doubly bad because Garmin assumed I had only slept until the point at which I took my watch off, not from when I bed until the point at which I put it back on, I finally managed to solve sleeping by rotating the watch so the face was on the inside of my wrist rather than the back of my wrist. I’m a stomach sleeper, and with the watch in this position, I was mostly able to forget it was there. Now, some six months later, I don’t really mind it too much, though I think Garmin absolutely needs to match Samsung and – rumor has it – Apple by making a ring. As Oura has pretty clearly demonstrated, you can fit all this technology in a ring, and that’s unquestionably the most comfortable form factor for sleeping. The disadvantage that Oura and Whoop have when competing with Garmin here is that they only have the heart rate data. They don’t know things like pace or watts. I think Whoop and Oura will struggle to make real inroads against not only Garmin, but also Polar and Suunto, which also are able to use information from connected sensors to enhance their understanding of training load. But form factor matters a lot. If I hadn’t committed to exploring this ecosystem fully, I would have given up after a few rough nights. I want the Garmin Ring. And I’m actually semi-surprised that it doesn’t exist yet. I think part of this is Garmin’s deep roots as a GPS company. Garmin GPS is – and always has been – superb. The only times I’ve ever had issues with accuracy was back when Garmin used to default to “Smart” recording rather than 1s recording as the default. Smart recording is still an option, but it seems that it was set to 1s by default on my 965, though that may have been the result of pairing a powermeter early on. Given how many of Garmin’s core products exist without GPS these days, I think a smart ring is not impossible, and I’ll be immensely glad when it arrives. Until then, I made the sacrifice to sleep with my watch on in the name of scientific discovery.

Training Load And Training Readiness.

It takes a few days of overnight wearing to incorporate the sleep data into Training Readiness. And then even longer for Garmin to establish an HRV baseline. But once you’ve worn your watch continuously for about a week, you’ll start to see the full Training Readiness data populate. This is based on:

- Sleep, which is the result of your “sleep score,” which factors in total duration, deep sleep time, REM sleep time, and both duration and frequency of “awake” periods

- Recovery Time, which is in response to specific training activities

- HRV Status, which is determined by the relative value of your previous nights HRV “score” to your 7D baseline range

- Acute Load, which is not actually the specific load in terms of quantity, but rather its ratio to your chronic load.

- Sleep History, which is your 7d sleep score average

- And Stress History, which supposedly measures your intra-day stress levels, but which has basically only ever told me that my days are fairly low stress. Which is maybe a sign that I’m just inoculated against getting stressed out by virtue of having four kids or, more likely, that I’m quite fit and so my intra-day resting heart rate – what I suspect it’s actually using – is quite low. I found Stress History to be entirely worthless.

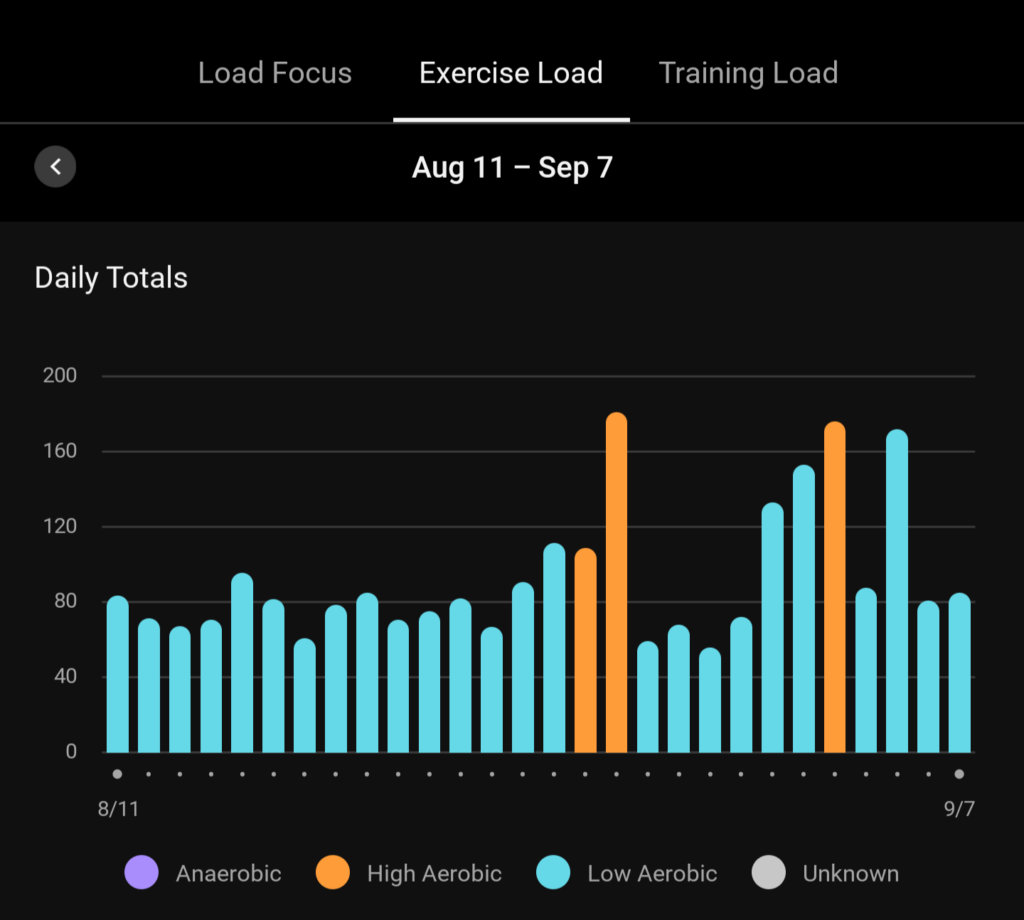

Of these, I found the Acute Load – and Garmin’s sense of training load – to be by far the most useful. I’ve used TrainingPeaks fairly religiously since 2014, and I think – especially for ultra-endurance training like Ironman, that TSS is generally quite useful. But one thing that I always felt it lacked – at least for me – was that it failed to capture the load of threshold and supra-threshold workouts effectively. I found that really, really hard workouts – longer time-trials, anything over 30min in particular – would take me at least a week or more to fully recover from. And yet in TrainingPeaks they just showed whatever the TSS for that workout was. A 30min TT was no more significant than an easy 3hr ride. But with Garmin, those hard workouts were reflected dramatically. I did a hard Zwift session that involved a near-maximal effort on Alpe du Zwift, and Garmin had a training load score for that workout that was through the roof. Note that Garmin generally only calculates training load for workouts recorded on Garmin devices. There are some very special exceptions here with special partners – like Zwift. But you can’t just upload any ride with HR data and get training load information from it. Notably, Garmin doesn’t actually care about power when calculating load. Only HR. But it was very interesting to see how dramatically Garmin scored sustained periods at/above threshold as compared with TrainingPeaks. For me, this was the first real indication that there was real utility in the FirstBeat analysis.

While I’d previously been skeptical of sleep trackers, the sleep measurements help cement something that I had intuited but only fairly casually. I saw a marked difference in sleep quality between nights when I was in bed before 9PM (I get up around 5am) and nights when when I was in bed after 9:30PM. Even if I managed to sleep in a bit, the quantity of my measured deep sleep – which Garmin reports as occurring very early in my sleep cycle – are markedly different. If I go to bed early, I get a lot more deep sleep, which helped explain to me why even if I got an equivalent amount of total sleep, I felt so much better with an early-to-bed-early-to-rise approach. And this became emblematic of my relationship with my 965. It has a lot of opinions. Many of these I disregard. But I do not entirely ignore them. If I sense there’s a nugget of wisdom or truth, I try to isolate that part, make use of it, and chuck the rest. I did not rely on it telling me what to do. But I did find it helped me to make better decisions about what to do.

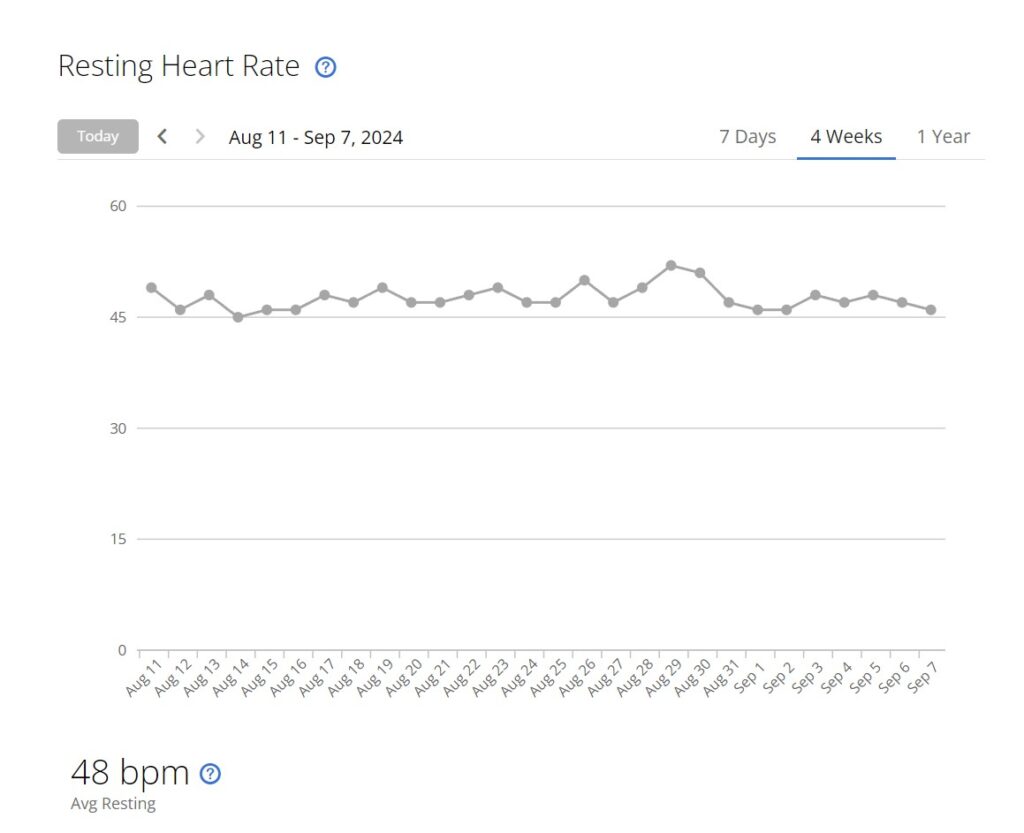

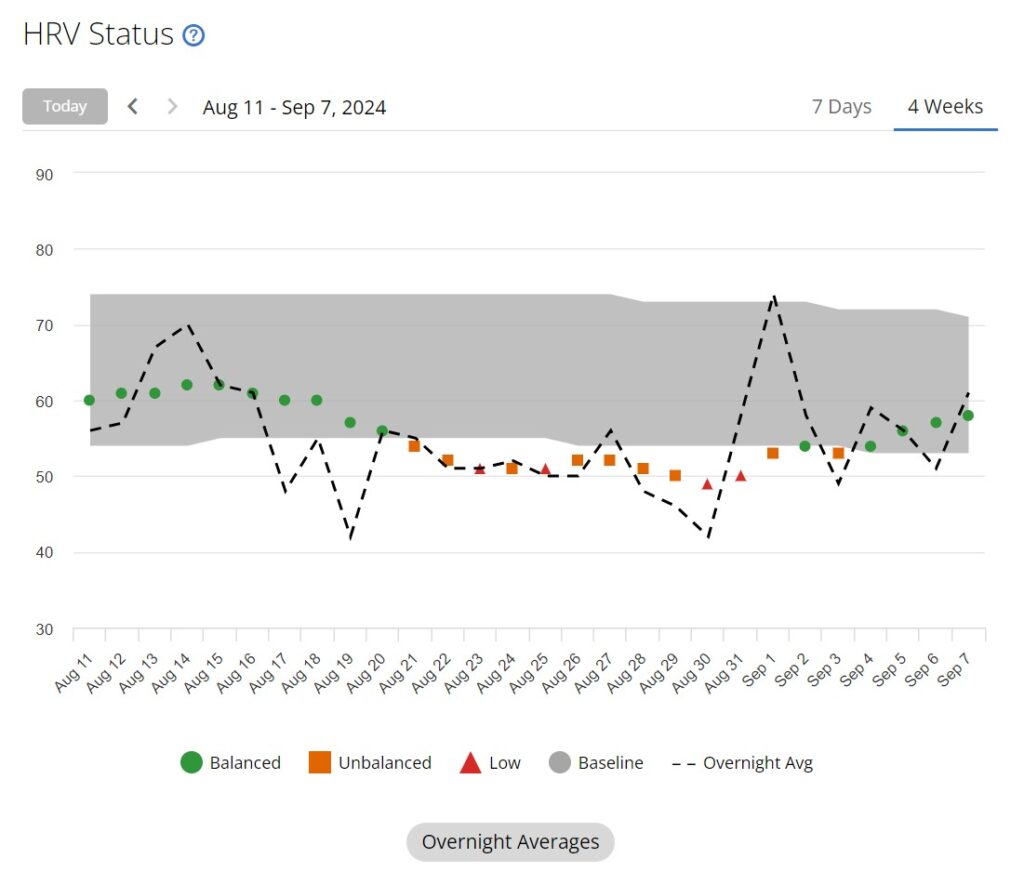

HRV vs RHR

My skepticism about the usefulness of HRV is largely unchanged however. It seemed to correlate almost exactly with overnight resting HR, something which is much simpler to understand. HRV did reflect that harder training sessions later in the day tended to impact my recovery, but I saw that exact same data in my overnight RHR and sleep score. I came away from this experiment with a better sense of what HRV actually shows and how it might be used – certainly much better than my 2013 experiment in the early days of HRV when I tried to use a system based only around intraday orthostatic tests (which you can take using the “Daily Health Snapshot” feature), but it still feels redundant to the classic RHR. My fundamental opinion of HRV – that it only tells you what you already know – is largely unchanged.

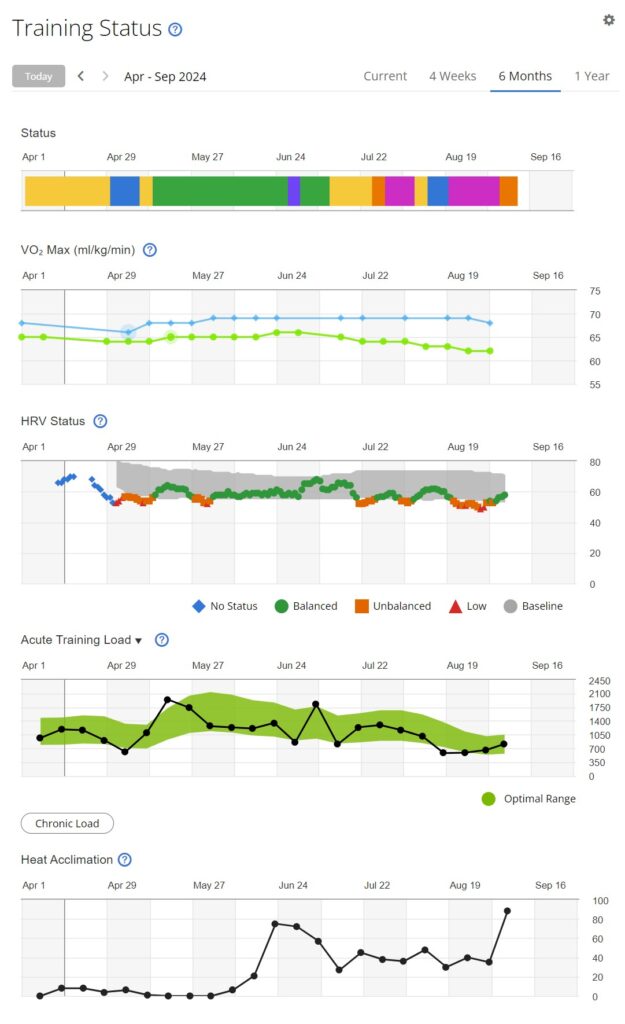

In addition to Training Readiness, Garmin also provides Training Status. Training Status is designed to provide insight on your training over the long term, whether your fitness is generally increasing or decreasing. There are eight distinct training status states, each of which has a helpful but brief description as to what it is meant to indicate; they are listed on Garmin’s dedicated tech page for the Training Status feature.

Sub-Disciplines Are – And Are Not – The Same Sport

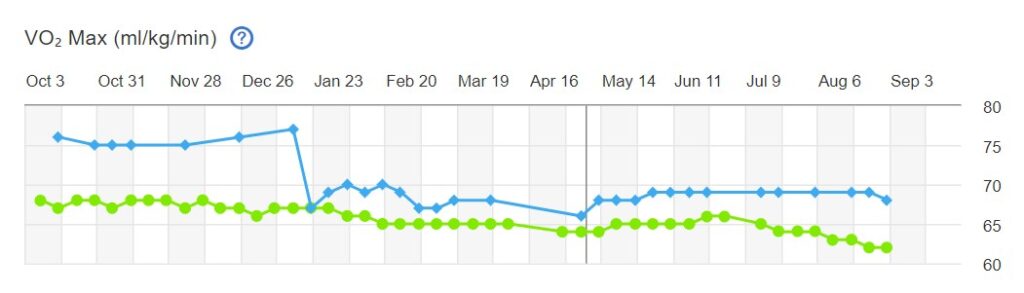

These are based off of VO2Max estimates, HRV data, and Acute Load (again, the ratio with chronic load). In general, I found these to be useful with a couple major caveats. And this is where my sense of what Garmin was – and more importantly was not – useful for started to emerge. On the running side, because it’s based on pace, I found that incorporating a lot of trail running would very much skew my metrics. That’s because there’s no ability for Garmin to reason about “technical” trails. Likewise, very steep trails – especially when descending – tends to throw NGP (normalized graded pace) for a loop, especially if those trails are also technical. On the road, I think there’s a very clear correlation between pace and fitness. That is also true when trail running, but the numbers are not equivalent. And this is really the biggest weakness of the FirstBeat approach. It treats all subcategories of a sport as the same. I.e., if you go for an easy 5K on the road at 4:30/km and your HR is 125bpm and then do an easy 5K on the trails at 5:00/km and your HR is 130bpm, that’s a sign of “decreasing” fitness. It does use NGP – so it accounts for the hilliness of the route, but it cannot account for the technical nature of running, nor does NGP work well, in my experience, for steep stuff. For running, this sort of okay, because you can opt-out certain sports from VO2 estimates. Once I told Garmin not to consider my trail running activities when calculating my running VO2, I found the data was much smoother, but also substantially less useful. My trail runs still counted towards my overall load, but Garmin could no longer reliably infer fitness gains from a fast trail run, because that run would often be relatively slow compared to a fast road run.Especially for someone with less experience training – I fundamentally know what works for me as a an athlete after 25 years of elite endurance sport, that could be incredibly confusing. And while you can wholesale discount certain sports, there’s no way to tell Garmin to ignore a specific activity, at least for VO2 purposes, or to possibly override it manually. This means that your HR monitor better be reliable. Thankfully, the built in Elevate 4 sensor is incredibly good. It’s actually shockingly accurate most of the time. But I still wear a chest strap for most of my training. But I had an older heart rate strap that I was using early in the year that had started to go on the fritz, and I would sometimes get periods of wildly high heart rate. This both dramatically increased my training load score and also resulted in Garmin assuming my fitness had tanked. And there’s literally no option to override values. Here’s where something like TrainingPeaks, where you just edit a workout and punch in a score for TSS is clearly superior. Garmin alludes to FirstBeat being able to detect aberrant data, but I would not say I found that to be the case. Maybe egregiously bad data, but not data that’s not impossible but is certainly implausible.

Unfortunately, this same locked-in approach is even worse with cycling. If you have a powermeter, Garmin gives you no option to opt a discipline out of cycling VO2Max. But I was training for XTerra. And I am not a particularly skilled MTBer. Especially on technical trails, my HR:power ratio is very different from what it is on the road. This was initially exacerbated by the fact that the Rally pedals I received, according to a static torque test using my tuned 20kg (+/-5g) mass that I have specifically for calibrating my powermeters indicated that the Rally’s were tuned about 2% low out of the box. And then, checking my Quarq, it seemed that when I’d switched from a gravel specific 42T ring to a road specific 50T ring – I run 1X on all my bikes, in spite of Quarq saying recalibration when swapping rings is not needed, my Quarq was 2% high in that same test. Once I got both powermeters in line with each other – and confirmed that they reported the same while riding, things were closer, but my HR was still higher MTBing. That’s partially because I’m not a great MTBer. But I also think fundamentally MTBing is more generally taxing than road riding. TrainingPeaks allows you to set a different FTP per discipline. But not Garmin. Cycling is cycling just like running is running. But that’s just not true. Ironically, realizing the overall utility of HR made me feel pretty good about simply taking power off of my MTB. While I couldn’t chose to opt out if I had power, I could opt out by simply not connecting to those pedals or by just putting my regular Shimano SPDs on.

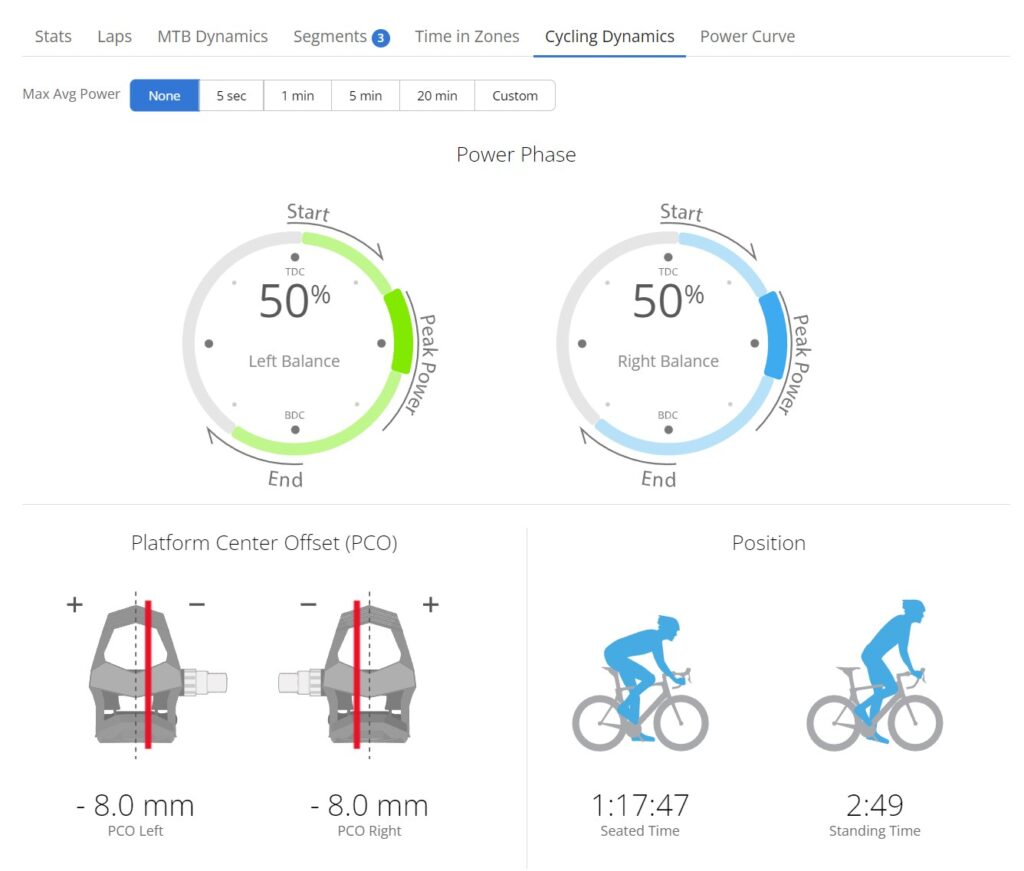

The Rallys are an interesting proposition. They’re substantially more expensive – just over $1100 – than their direct competition, the Favero Assioma – just over $700, which also allows for pedal body switching and is also rechargeable. The Rallys really only make sense within the context of the Garmin ecosystem. In Garmin connect, if you have Rally pedals, you get a ton of incredible information about how you ride. Time standing vs seated, especially relevant for gravel and other endurance racers. Average cadence standing vs sitting. Power balance data but also information about where in the pedal stroke you apply power with each leg. Is this data useful or actionable? I’m not entirely sure. I have nearly identical L/R balance, and while I found the data on seated vs standing fascinating, I also wasn’t really sure how I could use it in a meaningful way. If you’re a data geek, the Rally pedals are phenomenal. They were bombproof in terms of reliability, and they offer real information about how you pedal. And, if you’re viewing all of this in Garmin Connect anyway – as Garmin is pushing you to do, then it’s a one stop shop. At 5mm taller (10mm total thickness increase) than the absurdly thin Shimano XTR pedals, they are thicker than the Assiomas as well, but only a bit. I didn’t have any times where I clipped a rock that I thought was solely due to the pedals. But ultimately, I was put off of using them for a few reasons. The first is a bit unique to me, though I suspect I am not the only person in this situation. I think that, fundamentally, you need to stick to a single system for measuring power. It’s clear now that power is less clearly reliable than we’ve been led to believe. And it’s certainly less transferable. If you are a Quarq user, stick to Quarq. I personally believe that spider-based powermeters are the most accurate. Even after recalibrating both devices, I found the Garmin pedals read low relative to my Quarq during “bursty” efforts. Interestingly I also found that my spindle-based Quarq also read relatively low. Spider-based powermeters just seem to be the most responsive to quick accelerations. Which is not surprising. They are the closest to the source. There’s a reason Uli Schoberer developed the SRM as a spider-based unit and that remained the gold standard – and may still be the gold standard – for accuracy. The chain deflecting the spider is how power is actually applied to the drivetrain. Everything else is further removed. Some of this is self-serving, certainly. I like that my Quarq tells me I’m stronger than the Rallys do. But I also trust my Quarq data because, over 15 years, it’s been incredibly consistent, and also matches up well as compared with what elevation analysis and the simply static torque tests reveal it should be reading. I’ve also owned a lot of Quarqs over the years, and they’ve all matched up with each other. Pedal-based power measurement is hard. You have two devices that need to be reconciled against each other in real time. This is not trivial. Ultimately, I don’t think this really matters, though. The Quarqs are accurate. And the Rallys are accurate. But I do not think they are transferable. Pedal-based powermeters are amazing for portability. If you have a MTB and a gravel bike, something like the Rally makes a lot of sense. If you’re a data geek, and you just love all that information – regardless of utility, the Rallys are amazing. But for me, especially trying to focus on the ecosystem as a whole, I found they were hard to integrate alongside a Quarq on my road bike.

I think this is where the heavy restrictions Garmin places on treating all disciplines as the same is really the biggest miss. If I could have a different FTP on my MTB than on my road bike, which seems entirely reasonable – specificity is a thing, then I think I would have used the Rallys much more. If I do decide I want power on my MTB, most likely as a requirement for use with a Flight Attendant-enabled fork, I will likely choose to use a Quarq. My power numbers are Quarq numbers. Trying to mix measuring devices and disciplines just proved ineffective. The lack of power universality is also plainly obvious with running. I have a Stryd footpod, and I think it’s reasonably useful in certain scenarios, mostly hill training. I also think it’s reasonably “accurate,” though the precise meaning there is certainly more nebulous than with cycling. But at the very least, I found my running FTP was fairly close to my cycling FTP. Which makes sense. And which jives with other endurance sports. My rowing FTP is lower still, but still within range. Current higher end Garmin watches will estimate power from the wrist. I found this number to be useless, as it was entirely out of line with anything that seemed reasonable – i.e. doing 400w+ on an easy run. Now, maybe if I had nothing to compare it to. But knowing both what Stryd had said and what I felt was reasonable just understanding physiology, I couldn’t comprehend that power numbers it was reporting. I promptly disabled this and essentially never again thought about it after day 1. I don’t really think that running power is a “thing,” and my experience here confirmed that. Perhaps further proof that with power, you need to pick a single system and stick with it.

Now, having opted out my MTB rides from my cycling fitness evaluation and having opted out my trail runs from my running fitness evaluation, it might seem like I was dealing with a hamstrung system. But I actually found it to be quite the opposite. I think that the granularity of daily VO2 measurements was possibly noisy. And eliminating certain activities allowed for a smoother picture of fitness that was easier to interact with. My training data seemed very accurate. During a period when I took a week off from work and did a lot of training, Garmin warned me I was overreaching. Tapering into XTerra Victoria, Garmin quickly recognized that I was shifting back and forth between Recovery and Peaking. Ultimately, I came to very much value the insights that the Garmin ecosystem was offering.

Easy Really Should Be Very Easy

The biggest sign of the system’s utility was that I explicitly changed my training in response to what Garmin suggested. For easy runs, Garmin suggested a much lower HR – 125bpm – than what I would have otherwise considered. And I found those runs to be much more rejuvenating than ones that seemed only marginally harder – say 133bpm.

Garmin’s Daily Suggested workouts follow a similar theme of being useful suggestions, but not necessarily prescriptions. Interestingly, for base workouts, they simply prescribe a duration and suggested HR. No warmup. No cooldown. Early on, I would choose to do these, but stopped after I got tired off my watch “alerting” me that I was not in the proper zone 1min into my run. If you do want to use the suggested workouts, start them once you’ve properly warmed up. Weirdly, interval workouts do have a suggested warmup and cooldown period, though they are – in my opinion – unreasonably strict. There’s no concept of a progressive warm-up or cooldown, which is unfortunate because I think the fundamental suggestions are sound. I ended up using the suggested workouts more as reminders to not just do base and low aerobic. In particular, combined with the very useful load distribution chart – which categorizes your prior four weeks of training into three buckets – Anaerobic, High Aerobic, and Low Aerobic, I found this to be incredibly useful for getting back into race fitness. This is again where TSS falls flat. TrainingPeaks does give you insight into time-in-zones, but Garmin’s three zone system is very simple. I had fallen into a habit of doing almost all low intensity work, and I noticed a dramatic fitness boost especially from incorporating more “high aerobic” work. This is what really impressed me the most about the Garmin system. I did sense real insight. There were some maddening parts as well – if you are a triathlete, it offers both bike and run suggestions, but only assumes you ever train one sport in a day. Now, Garmin does offer proper “training plans,” but with a busy job and a young family, I like the flexibility of having a loose schedule. And so the suggested workouts are nice. But it would be nice to see the system be a bit more responsive to doing multiple sessions in a day. As seems to be generally true of AI systems, they work best as a junior assistant.

When The Data Is All You Have, Garbage Is Especially Bad.

As with any system that is entirely reliant on data, bad data is a problem for this system. This is where I wish Garmin offered better manual overrides. Nowhere is this more true than with swimming. While the 965 does measure HR while swimming, it admits that it’s only semi-accurate. If you want to get good HR data, you must use either the Pro strap of the Tri/Swim strap from Garmin. I did not – and I’m still undecided about wearing a HR strap while swimming… – and this is certainly the biggest miss in my evaluation of the system. My swimming load was generally very low, as is typical with optical HR sensors, when they are off, it is almost always that they read too low. Even during hard swim sessions, I’d often get a final average heart rate of barely above 100. And during threshold efforts my HR would register in the 120s or 130s. This meant swim workouts got dramatically undercounted in terms of the load they applied. I think if you really want to rely on this system as a triathlete, the swim-specific strap is a must. But I think it also shows the inherent weakness in a system where data is all there is. Wonky power or HR data can cripple such a system. The auto-detect max-HR feature worked fine, regularly reporting that my max HR is about 180. But when I wore the 965 – without a strap – during XTerra Victoria, the run data was wildly inaccurate, reporting that my average HR was approximately 190+ bpm for the entire run. For two weeks after this, after every workout, Garmin would constantly tell me that based off of historical data, it was changing my max HR to 196. I eventually disabled the auto-update maxHR feature as well.

In addition to struggling with HR accuracy, I also found lap counting to be another case of almost-but-not quite. I would say almost 100% of my swims the 965 would miscount a length or two. This was simultaneously impressive and incredibly frustrating. That the watch is properly able to identify send offs and stops with near stopwatch accuracy is remarkable. The fact that it randomly will decide that I did a 375 instead of a 400 was also super frustrating. I did learn that you should always check the compass app for accuracy before starting a swim, and do the figure-8 as you would with your phone to calibrate it if it’s wonky. This alleviated almost all of my swimming woes. And swimming LCM, the Garmin is essentially perfect, but in a SCY pool, I found that almost every swim it would short me a length here and there. Did this really matter? No. But what was so frustrating here is that Garmin offers you zero tools to correct this. Want to edit that 375 to be a 400 in Garmin Connect? No can do. There are numerous forum threads about this with Sisyphean solutions that involve various third party sites to do FIT file editing. I just ended up adding a drill block in at the end of my workout to add the extra 25 or 50 back in so that my count would be correct. I could have certainly ignored it, but I suspect I’m like most triathletes in terms of being neurotic enough that this is simply not an option. Again, it’s 99.9% accurate. But in some ways being so close almost makes the random dropping of a 25 here and there feel worse. It’s like, “why that rep?” But I can acknowledge that I’m only nitpicking because fundamentally, the system really does just work and counts and times your laps with incredible precision without you ever once needing to touch a button. Which is remarkable.

Overall, the system being so good means it’s incredibly reliable and useful over the long run. Individual outlier data does eventually get smoothed out. But I think that also magnifies the times that the system doesn’t work. One night, my watch got positioned badly, resulting in an abysmal sleep score, which then drastically reduced my apparent training readiness. I just ignored it, but it was another reminder that these quantified self-devices are there to help you make good decisions, not to make decisions for you. The system mostly does just work. But I don’t think you can just cede control over your training to it. The Garmin ecosystem was at its most useful when it was just another data point – or points – that I was able to meld with experience in order to keep my training both enjoyable and productive. Your watch can’t know if some days you just need to let it rip. And some days you just need to chill. Though I did find it remarkable that sometimes it actually compelled me to be honest with myself and to actually do those things when maybe I hadn’t really thought I was up to it. While it mostly succeeded in helping me go easy more often, there were also some times when I used an indication of high training readiness to let it rip, and those workouts – though they were few – were always good.

My Two Favorite Features – Heat Acclimation And Self-Assessment

The two features I actually came to enjoy the most appear to have no particular impact on the larger system, though I think they can and should. The first is the Heat Acclimation score. This would have been incredibly value when I was preparing for Kona or other hot races. The score is based on time training above 22C (which honestly feels a bit low to me), but overall, I found it to match up extremely well with my own experience around adapting to the heat. For workouts in warmer weather, it will tell you how much that workout increased your relative heat acclimation (out of 100%) and your overall acclimation. What’s especially interesting is how quickly it would dissipate. This gave me some solace about my 2013 DNF in Kona, when I missed doing my normal heat training block in the leadup to the race as I was sideswiped by a car and had to take a few weeks very easy to recover. I didn’t think I lost too much fitness, but I ended up overheating early in the bike and then dropping out on the run. Seeing the quantification of that heat training data on the 965 made me think back to that time in the heat that I missed and how quickly my acclimation would have faded. And how much time it takes to come back. The data here isn’t as good as what I think you get from CORE – or, perhaps, from the Epix’s Elevate 5 sensor that also considers skin temperature, and it also doesn’t account for humidity or the additional thermal load of something like riding a stationary trainer, and yet I can say that once my heat acclimation score was above 50%, I was a lot more comfortable in the heat. If you are preparing for a hot race, using this as a guide to make sure you are properly adapting to the heat would be very useful. I actually bought a Garmin external Tempe sensor – since discontinued – to get temperature data on my watch back before the altimeter (which also provides temperature data0 was standard on the Forerunner series. But actual heat training response is orders of magnitude more useful. While I think temperature is necessarily reflected in training load, I did think that Garmin could do a better job of accounting for this in terms of training status. If the weather suddenly turns hot and your VO2max, by default, drops due to being less fit in the heat, that doesn’t mean that training suddenly is Unproductive. This is where only using VO2max as a measure of fitness falls short. I hope Garmin figures out how to incorporate the heat data more broadly, as I think it is a miss to have it exist essentially as a standalone metric as it does now.

Interestingly, my favorite feature of the 965 appears to have not actual impact on anything. Though I found it to be incredibly useful as a habit builder. And that’s the post-workout RPE self-evaluation. After a workout, you score the RPE on a 1-10 scale from very light to maximal. And then you give a self assessment about how you felt on a 1-5 score from very weak to very strong, indicated by smiley (or frowny) faces. I love this. And the utility of this is well established. Self-evaluation – both in the moment and over the long term – is incredibly insightful. And, critically, it forces introspection. I found myself being more honest. And then I found myself using those evaluations to make decisions about whether or not to do a second workout. Or, having decided to do a second workout, how hard to make it. This, more than anything else, is my favorite feature of the current crop of Garmin watches. I’d love to see this data be presented in a more usable way – in particular, how has my 1-5 subjective eval tracked over time. But it’s only available currently on the individual workout screen.

The Ecosystem Hub – The New Garmin Connect

Thankfully, the data is there, and it’s just a software update away. And this brings us to Garmin Connect itself, the hub – newly reimagined – for all this data. In a running theme, Connect still has an almost-but-not-quite feel to it. Notably, the web app and the phone app have wildly different UIs. Finding data in one place on one app does not mean you will find it in the same place on the other app. There were also some very weird decisions about what is permanent. I have not played a round of golf in over 20 years. I have zero interest in golf. I do not own a Garmin Approach watch. I do not want to think about golf in any way. And yet Golf is a permanent and fixed section of the primary menus on both the web and mobile apps. I can’t view my long term RPE data but I’m forced to think about downloading golf courses. Does this really negatively impact my experience? No. But at the same time, I felt it highlighted the frustrations I had with needing all of these clicks and taps to view my training data and then thinking, “why is it one click to download a golf course?” Especially coming off the big overhaul, this felt like such an obvious miss. Pick your sport/athlete type and then just tweak the UI accordingly. It just felt like it was designed to undermine Garmin’s credibility with endurance athletes. For as amazing as the system is, it’s things like this that just make it harder to really trust.

I also think that Garmin is in danger – as Strava was as well – of trying to make Connect too many things. It’s added badges and challenges. I got a recent email from Garmin letting me know I could “have more fun with Connect!” Garmin has recently rolled out some straight up copy-cat Strava features that I just don’t think make sense. I understand that Garmin wants an ecosystem, but it can’t be all the things. I think Strava has wisely walked back – or at least de-emphasized – many of its features that seemed designed to compete with Facebook and Twitter. I don’t think Connect needs to replace Strava. While Strava does dabble in training data – and I do consider it dabbling, it’s not their core product. And while maybe some of the social features Garmin is introducing into Connect will likewise be “dabbling,” I wonder if those features are more meaningful than, say, the ability to remove Golf from your home screen…

Overall, my criticisms of the Garmin ecosystem are minor. And if history is a guide, the system will only continue to get better. Garmin’s track record of near constant and continuous improvement is exemplary. Having worn the 965 for over six months straight, only taking it off to charge – which is rare, as it has incredibly long battery life, I can say that I have found it to be an incredible ally in managing family, work, and training for my first triathlon in seven years. In that time, I certainly had my frustrations. But as someone who has worn nearly every revision of the Forerunner, from OG 201 up to this latest and greatest 965, seeing the evolution of not only the Forerunner as a watch, but also the Forerunner as part of a system designed for endurance athletes has been remarkable. When you buy into a system, a device becomes more than its specs and list of features. I arrived at the start line – and then the finish line – of XTerra Victoria fit, healthy, and happy. Most of that was the result of experience. But some of that experience was directly informed by feedback and information provided by the Garmin ecosystem. When Garmin first started incorporating FirstBeat data into its analysis of its user’s training, it became an instantly different company. Suddenly, it had opinions. I set out to discover, after nearly 15 years, whether any of those opinions were any good and worth listening to. I was initially very skeptical that it could teach me anything new, but I was open minded to the idea. And after half a year, I can say unequivocally that I believe it can help you make better decisions. I am even more convinced that you need to be the one making decisions; do not hand over the reins fully to these systems. They are not a replacement for a coach. But they are also not inherently worse. They are different. A coach comes with accountability. That is the most valuable and important thing that a coach offers. But that also comes with a cost and with potential downsides. Garmin is easy to ignore when you want to. There are countless memes about all the ways in which your Garmin is judging you. But I think it’s more trying to “care” for you. It just wants what’s best for you! And sometimes, I think it’s right.