I feel obliged to write a little something about this since I see soooo many replies in this thread where people have been completely mislead by their medical professional. I’m a final year PT student with a special interest in pain science, tendinopathies, movement in general and sports and triathlon in particular.

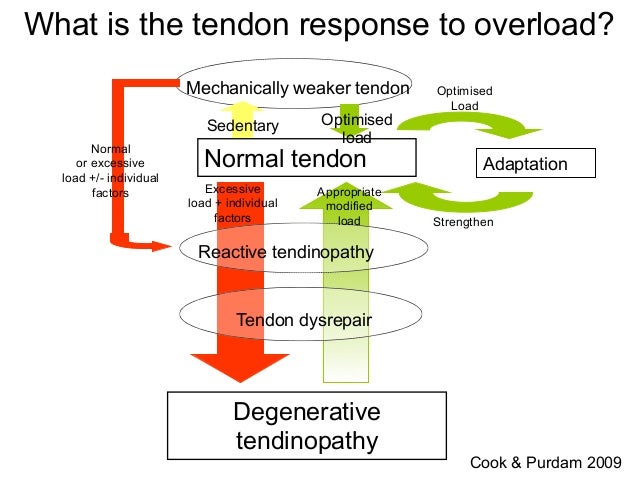

First let me explain Jill Cook’s continuum model about tendinopathy:

As you can see, a tendon that has been put through more load than it can take will become reactive. This is what many of us athletes have felt when ramping up swimming or running volume: our shoulder/achilles start hurting. It’s a load-induced hurt and the pain is usually 0/10 in rest. Taking a few days off, maybe some ibuprofen and like magic, its gone. That is “appropriate modified load” for the reactive tendinopathy.

However if one continues to apply excessive load, or if any other individual factors becomes worse, the tendinopathy will not resolve by itself and will enter a dysrepair/degenerative phase. This is often called “chronic” tendinopathy because it’s much tougher to get rid of, but as you can see looking at the model “appropriate modified load” can get you out of the degenerative phase as well.

So what loads a tendon?

Tendon is loaded by movements, and there is 3 types of load we can apply to the tendon.

The first, most basic load is tensile loading; this is simply done by flexing the muscle that inserts into the tendon. This is generally well tolerated even by a degenerative tendon. The amount of tensile loading is proportional to the muscles contraction (add weight and it’s more loading). An example for achilles tendinopathy is to just raise your heel 1 inch off the ground, standing on your toes. A easy way to quantify this type of load is to start with isometrics and count time under tension. Isometrics might also immediately reduce tendon pain through a mechanism way out of scope for this text, but its a cool thing to try. A good isometric for proximal hamstring tendinopathy is the supine bridge.

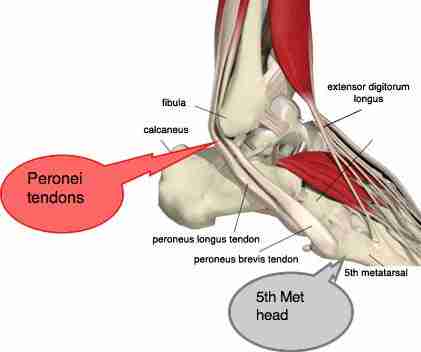

The second type of loading is compressive loading. This is when a tendon wraps around a bony structure and is put under tensile loading, compressing it towards that bone. A good example is the peroneal tendons, wrapping around the lateral malleolus:

This type of loading is often aggravating for tendons. The reason is also beyond this text. Here is a pic which describes where the common tendons are compressed.

The third type of loading is energy storage; what tendons are best at. This is also often aggravating and especially if it is combined with compression (like the peroneal tendons or distal achilles tendon when running). This type of loading comes from a passive lenghtening of the tendon from an external force when the muscle is ‘locked’ isometrically. Think of the calf complex when running; the calf will contract isometrically but the foot will reach maximum dorsiflexion at mid stance; this loads up the tendon with mechanical energy that will be released at toe-off.

So this gives a very basic understanding about what tendinopathies are; an inability to tolerate the current load. By modification to this load, we can create adaptation and get the tendon functional and pain-free again. How long this takes depends on how long you’ve had the tendinopathy, individual factors (training response, morphology, psychological factors, etc) and how much demand you will put on your tendon.

So how does one start rehabing a tendinopathy?

Step one is to find your current load tolerance and build from there. Start with tensile loading out of compressive positions. For the foot’s tendons this means maximum plantarflexion, for the proximal hamstring tendinopathy it means maximum hip extension (since the tendons wrap around the ischial tuberosities when the hip is in flexion, such as in the time trial position or when you sit on a chair. Sitting also increases compressions since well, you sit on it). Start with an isometric program only for a few days and see if this calms the tendon down or aggrevates it. If you tolerate it, start doing some actual movement. If you dont, reduce load. Keep track of what you do and add in more exercises the more you can tolerate. When you can do pretty much, start adding in some compression. When you tolerate this, add in energy storage. It’s all simple in writing but takes time, tears, commitment, experimentation. It’s like ironman finish times; easy to do it fast on paper.

An example progression of exercises for proximal hamstring tendinopathy could be this:

W1: 3x30s supine bridge, adding some time daily

W2: 6x45s supine bridge with extended legs, feet resting on something

W3: 5x60s suping bridge, feet up + 3x10 ball curls

W4: 1x60 supine bridge, 3x10 ball curls, 1x10 dynamic supine bridges (glute bridge)

W5: 4x10 ball curls, 2x10 glute bridge, 1x10 one-leg glute bridge

W6: 3x10 glute bridge, 2x10 one-leg glute bridge, 10 one-leg straight leg deadlift

W7: 2x10 glute bridge, 3x10 one leg glute bridge, 2x10 one leg straight leg deadlift

W8: 3x10 one leg glute bridge, 3x10 one leg straight leg deadlift, 3x5 deadlifts

Somewhere in there one can also start running, it’s energy storage but with pretty little compression.

Hope this gives some insight and also makes you question all the passive modalities that it seems like every PT/GP/Chiro prefers here in the US (injections, dry needles, different ways to hurt you with tools like graston/art whatnot). A tendon needs load, a tendinopathic tendon needs smart, well progressed load. Good luck!